7 Feb 2026

- 0 Comments

Paris has long been a city of allure, art, and secrecy-and for centuries, escorts have played a quiet but powerful role in its social fabric. Not the kind you see in modern ads or dating apps, but the real, complex figures who shaped Parisian culture, politics, and even art. From the glittering courts of Versailles to the dim-lit alleyways of Montmartre, escorts weren’t just companions-they were influencers, spies, and sometimes, the only voice women had in a man’s world.

Medieval Beginnings: When Sex Work Wasn’t Illegal

In the 13th century, Paris had over 100 licensed brothels, officially called parloires. These weren’t hidden dives; they were regulated by the city and taxed by the crown. King Philip IV even set rules: brothels had to be outside city walls, women couldn’t wear veils, and clients had to pay a fee just to enter. The most famous was the Châtelet district, where women from across Europe gathered. Some were runaway peasants, others were widows with no other means of survival. A few became wealthy enough to buy property. This wasn’t crime-it was commerce.

The Courtesans of the Renaissance

By the 1500s, Paris saw the rise of the maîtresse en titre-official mistresses to kings and nobles. Catherine de’ Medici, queen of France, kept her own network of women who acted as go-betweens in political deals. One of the most powerful was Diane de Poitiers, who wasn’t just Louis XIV’s lover-she controlled his spending, influenced his foreign policy, and even had her own palace. These women didn’t just sleep with power; they shaped it. They hosted salons where philosophers debated, artists sketched, and poets recited verses. A courtesan’s influence often outlasted her lover’s reign.

The 18th Century: Salons, Scandal, and Survival

Before the French Revolution, Paris became a city of salons run by women who doubled as escorts and intellectuals. Madame de Pompadour, Louis XV’s favorite, didn’t just charm the king-she commissioned furniture, funded artists like Fragonard, and helped launch the Rococo style. Women like her were educated, spoke multiple languages, and moved in circles that included Voltaire and Rousseau. They weren’t just paid for sex; they were paid for conversation, charm, and access. A man who wanted to climb the social ladder often started by becoming a regular at a courtesan’s table. The line between escort and socialite was thin-and sometimes, nonexistent.

Napoleon and the Crackdown

Napoleon Bonaparte didn’t like what Paris had become. In 1804, he shut down all licensed brothels, claiming they spread disease and undermined morality. But instead of ending sex work, he forced it underground. Women moved to neighborhoods like Saint-Germain-des-Prés and Pigalle, where they worked in private apartments, disguised as seamstresses or music teachers. Police records from 1810 show over 2,000 women registered as "women of ill repute"-a legal term that meant they were monitored, taxed, and forced to undergo monthly medical exams. This was the birth of state-regulated prostitution, not its end.

The Belle Époque: Glamour in the Shadows

From 1870 to 1914, Paris exploded into a glittering age of art and excess. The Moulin Rouge opened in 1889, and with it came a new kind of escort: the cabaret performer who also took lovers. Jane Avril, a dancer at the Moulin Rouge, lived in a luxury apartment on Rue de la Chaise and entertained aristocrats, writers, and even the future King Edward VII of England. These women didn’t hide-they performed. They wore designer gowns, drove carriages, and were painted by Toulouse-Lautrec. Their portraits still hang in the Musée d’Orsay. For many, this was freedom: control over their income, their image, and their choices. But it came with danger. Police raids, disease, and violent clients were constant threats.

Post-War Decline and Legal Shifts

After World War II, France began to shift. Feminist movements grew, and the idea of state-regulated prostitution became harder to defend. In 1946, the French government closed all remaining brothels under the Loi Marthe Richard. It wasn’t about morality-it was about control. The law didn’t make sex work illegal, but it made organizing it so difficult that most women were pushed into street work or private apartments with no protection. Many turned to pimps or criminal networks just to survive. The romantic image of the Parisian courtesan faded, replaced by headlines about exploitation and trafficking.

Modern Paris: What’s Left?

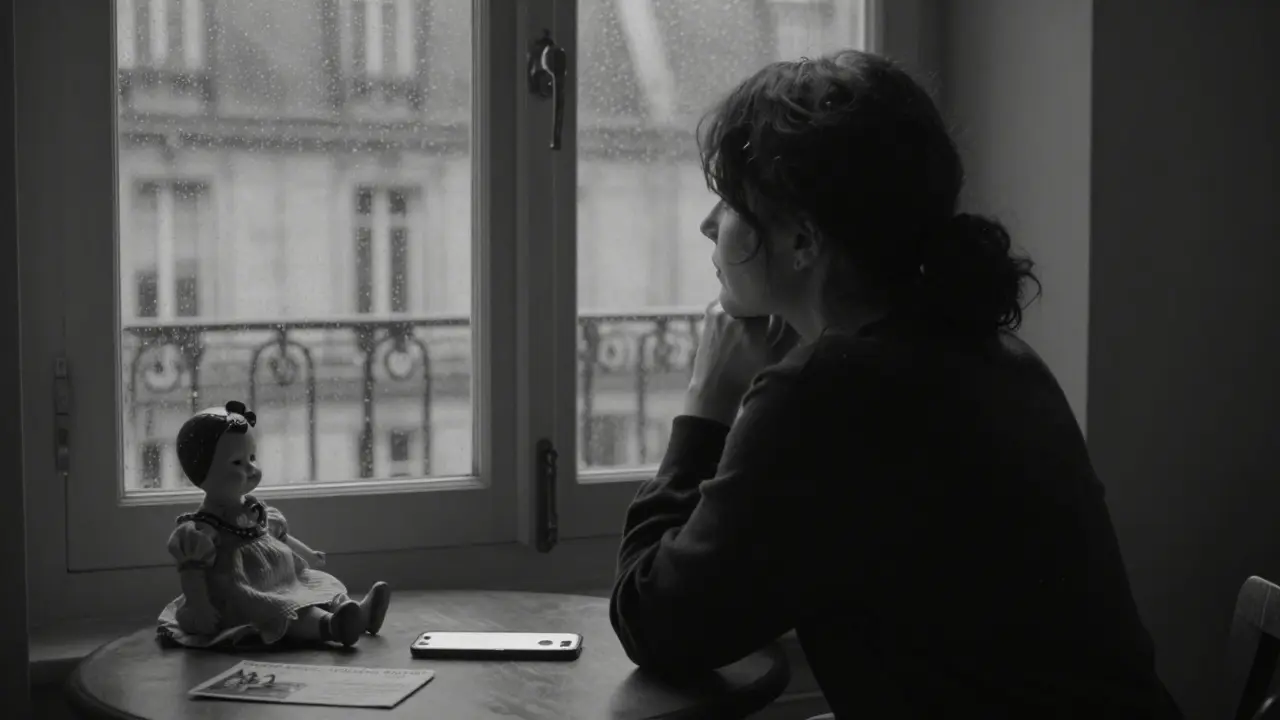

Today, prostitution in Paris is legal-but soliciting, pimping, and running brothels are not. This means you can legally sell sex, but you can’t legally work with others or advertise. Most women work alone, using apps or word-of-mouth. The old neighborhoods like Montmartre and the 13th arrondissement still see clients, but the scene is quieter, more isolated. The glamour is gone. The power is gone. What remains are stories: of women who once held court, who influenced kings, who turned survival into art. Their legacy isn’t in the brothels that closed-it’s in the paintings, the letters, the poetry, and the quiet defiance of women who carved out space in a world that never gave them much.

Why This History Matters

When you walk past the Place de la République or sit in a café on the Left Bank, you’re standing on ground once walked by women who shaped Paris in ways history rarely records. They weren’t just escorts. They were patrons of the arts, political players, and survivors. Understanding their history isn’t about scandal-it’s about seeing how power, gender, and survival have always been tangled together in this city. The modern escort industry may look different, but the same questions remain: Who gets to be seen? Who gets to be heard? And who gets to decide what’s moral?

Were escorts in Paris ever legally recognized?

Yes, for centuries. From the 13th century until 1946, brothels were licensed and regulated by the French government. Women working in them were registered, taxed, and even given medical checkups. The system was designed to control disease and keep sex work out of public view-not to eliminate it. The 1946 law, named after activist Marthe Richard, shut down all brothels, marking the end of official recognition.

Did any escorts become famous or influential?

Absolutely. Women like Diane de Poitiers and Madame de Pompadour weren’t just lovers-they were political advisors, art patrons, and cultural trendsetters. Pompadour helped launch the Rococo style and funded the Sèvres porcelain factory. De Poitiers controlled royal spending and influenced France’s foreign policy. Their influence extended far beyond the bedroom. Even today, their portraits and homes are preserved as national heritage.

How did the French Revolution affect escorts?

The Revolution didn’t end escorting-it changed it. Nobles lost their power, and with them, the traditional patronage system. Many courtesans lost their income overnight. Some became teachers, shopkeepers, or joined revolutionary causes. Others moved into underground networks. The shift from aristocratic patronage to commercial sex work began here, laying the groundwork for the modern industry.

Why were brothels shut down in 1946?

The 1946 law was driven by feminist activism and public health concerns. Marthe Richard, a former sex worker turned politician, argued that state-regulated brothels exploited women and didn’t stop trafficking. The law banned brothels but not prostitution itself. The goal was to protect women by removing the system that made them visible and controllable. In practice, it pushed many into more dangerous, unregulated work.

Are escorts still active in Paris today?

Yes, but differently. Prostitution itself isn’t illegal, but advertising, soliciting, and running organized operations are. Most workers today operate alone, using encrypted apps or personal networks. The old red-light districts like Pigalle are quiet compared to the 19th century. The industry is now largely invisible-no more cabarets, no more painted portraits. Just quiet apartments, late-night texts, and the same old struggle for safety and dignity.